FAQ: A beginner's guide to the ETS

What is the Emissions Trading Scheme and does it work to reduce emissions?

No idea what the ETS is? You aren’t alone. As dry as an emissions trading scheme sounds, we need to understand it in order to campaign for the right solutions to the climate crisis.

The Emissions Trading Scheme is one of the key policy tools that the New Zealand government is leveraging to achieve our commitments under the Paris Climate Agreement. So let’s get into it!

What is it and how does it work?

Emissions Trading Schemes like the one we have in New Zealand aim to create a market for greenhouse gas emissions. Basically, instead of letting companies emit for free and not charging them for their contributions to climate change, it puts a price on every tonne of CO2e emitted. The first ETS was established in the European Union in 2005. Since then, the model has gathered momentum worldwide as a way of reducing emissions.

The ETS in New Zealand is a “Cap and Trade” system. It has two key parts:

a limit (sometimes called a cap) on how much greenhouse gas can be put into the environment within a market area; and

tradable allowances (or units) that let companies emit a specific quantity of emissions. As time goes on, the limit/cap is slowly lowered, so fewer units are available. The cap can also be lowered in line with the emissions budgets we’ve set for our annual goals.

The theory is that if companies have to pay for emissions, it incentivises them to innovate to reduce their emissions to reduce costs. The money earned by paying for units can then be used to help with the climate transition.

Who has to participate?

In New Zealand, most companies above a certain size threshold must participate in the ETS. There have historically been exceptions like landfills, international aviation, agriculture, which are slowly being included / enforced.

We don’t all have to trade on the market for our emissions individually - companies above a size threshold in these sectors must calculate their greenhouse gas emissions, and for every tonne of emissions they release, they must buy & surrender (use up) a unit to the Government.

How do companies participate?

There are four main ways that participants in the scheme can buy “units” to cover their emissions (known as New Zealand Units or NZUs):

Buy directly from the Government: every 3 months, the Government auctions NZUs to the market.

Free allocation: for companies that are considered “Emissions Intensive, Trade Exposed” the Government will give them up to 90% of the NZUs they need for free. The reasoning behind this is to prevent something called “carbon leakage” - if New Zealand companies need to pay more to produce their products, they will be less competitive with overseas companies who don’t have to pay for carbon credits. They might therefore shift their production overseas to a country that doesn’t have an ETS or carbon market, and maybe has worse environmental protections. This is becoming less of a credible reason for most industry players as more countries are required to account for their emissions (see: Fonterra consumer pressure case).

Buy from the market: any company or person can buy or sell NZUs on the open market - so if a company doesn’t use all of its NZUs, it can sell them to another company.

Generate NZUs through sequestration: any company can create NZUs (which are equivalent to 1 tonne of Co2E) for projects that store or reduce greenhouse gasses from the atmosphere. E.g. If you own a forest that absorbs greenhouse gasses, then you can earn NZUs and sell them on the market. This is the main way that forestry participates in the ETS.

So… is it working to reduce emissions?

If it works well, an ETS can create certainty for companies about their future overheads and operational costs, trigger innovation for cleaner technologies, and generate funding for mitigation and adaptation against climate change.

However…this only happens if the price for credits is set at the right level. We don’t want to depress you, but globally only 5% of current carbon prices are at levels consistent with emissions pathways that fulfil the Paris Agreement targets, and less than 4% are at levels consistent with the emissions pathways of the IEA Sustainable Development.

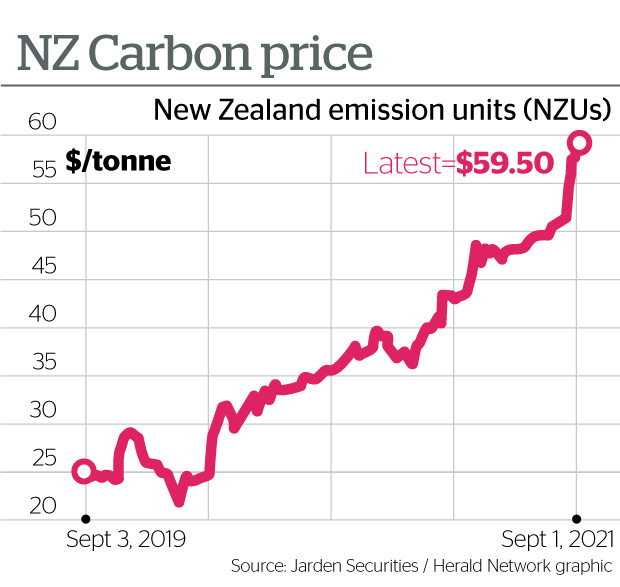

There have been many recent changes to the ETS which are improving its efficacy. In New Zealand, we are now finally seeing a rise in the price of NZUs which means the ETS is becoming more effective. As at 11 December 2022, the NZ carbon price is $88.50NZD per NZU and you can see the steep curve upwards since 2019 in the graph below.

However, there are still some problems with the NZ ETS that make it less effective at reducing emissions, including:

Free allocations: As you have probably guessed, if a company is given free allocations, they don’t have much incentive to reduce their emissions. What’s more, carbon leakage is becoming less and less of an issue as other countries and geographical areas also establish carbon markets, and adjust border taxes to ensure competitiveness. Free allocations were meant to be phased out by 2030, and there’s progress in improving the but the latest bill is also introducing a way of granting them to new organisations who qualify for them (more on this early next year).

A big surplus of credits: In the past, unlimited numbers of international and cheap NZUs were allowed to flood the market, meaning there is now a privately held stockpile of NZUs – around 150 million units or four (!) years of emissions. This means it's easy for companies to get a hold of NZUs to surrender to the government instead of making actual cuts. Auction volumes from the government have been lowered to try and reduce the surplus to zero by 2030.

Too much reliance on forestry: The ETS encourages using tree planting as a sequestration rather than making actual cuts in emissions. Additionally, because exotic species such as pine grow faster, we plant more of these rather than regenerating or protecting native forests, which has biodiversity implications.

Agriculture was historically not included: Currently, because the ETS does not apply to agriculture, which emits almost half of New Zealand’s greenhouse gas emissions. This is what the ‘Pricing Agricultural Emissions’ / He Waka Eke Noa process is proposing to resolve.

The cap is not a true cap: Currently the cap has ‘release valves’ when the price gets too high, which adds further units onto the market. The government has recently proposed increasing these bands before the cap is hit, but we would love to see the release of extra credits removed entirely!

The ETS is one tool in our toolkit

These issues are being resolved, but it’s a slow process. One thing we know for sure is that the ETS isn’t a silver bullet - even if it worked perfectly, it can only be one tool in our toolkit to solve climate change.

We can only achieve our climate ambitions if the ETS is working in combination with other climate policies like zero carbon acts, investment in public transport and electric car infrastructure, green financing, biodiversity strategies, implementation of circular economy and new ways of thinking about agriculture.